December 11, 2018

Selma Interpretive Center

The Selma Interpretive Center and the National Park Service Interpretive Center tell the story of those who nonviolently fought for the right to vote. These events occurred 100 years after the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments to the Constitution banished slavery, provided equal protection under the law, and guaranteed the right to vote.

The Selma interpretive Center chronicles the events leading up to Bloody Sunday, March 7, 1965 and the Selma to Montgomery March later that month.

Downtown Selma today

Even in 1965 literacy tests and poll taxes were used to keep blacks off the voter rolls. While some whites may have been hard pressed to pay their poll taxes it was especially difficult for the many blacks who were sharecroppers or tenant farmers and often deeply in debt to the white landowners. For those few blacks lucky enough to afford to pay the poll tax, most “failed” the literacy test which asked questions such as “How many bubbles in a bar of soap?” Other questions related to explaining arcane sections of the state constitution. Because these were oral tests the examiner determined who passed and who failed. As a result, few blacks made it onto voter rolls in the Deep South.

Still, groups of blacks continued to attempt to register to vote. They were almost always turned away, sometimes violently. These events eventually led to the Selma to Montgomery March.

On January 22, 1965, over 100 black Selma teachers marched to the county courthouse to register to vote. They were turned away but not until Rev. Frederick Reese was assaulted by Sheriff Jim Clark. Other groups of black professionals followed their example, bringing the issue of voting rights to national attention.

On February 18, Rev. James Orange organized and led a march of 125 mostly students to the courthouse where he was arrested. Rumors spread that he would be lynched. That evening up to 400 marchers headed toward the jail where Rev. Orange was being held. Police assaulted the marchers and accompanying media, forcing them to retreat. Some took shelter in Mack’s Café. Inside the café Jimmie Lee Jackson, a Vietnam War veteran and church deacon, was shot in the stomach by an Alabama State Trooper while protecting his mother and grandfather. He died on February 26.

At Jackson’s funeral, Rev. James Bevel said, “I’m going to Montgomery to see [Governor George] Wallace. And I’m gon’ walk if I want to.” The Selma to Montgomery March was born.

On Sunday, March 7, 1965, 600 blacks gathered at the Brown Chapel A.M.E. Church in Selma, Alabama and began a march to the state capitol in Montgomery, Alabama.

Brown Chapel A.M.E. Church

As they crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge they were met by Alabama State Troopers and local law enforcement volunteers.

Edmund Pettus Bridge

The marchers were given two minutes to disperse and after only one minute were violently attacked. Men on horseback, sheriffs’ deputies, and outraged whites joined in the assault using tear gas, police dogs, cattle prods, clubs, bull whips, rubber tubes wrapped in barbed wire, and metal pipes. None of the marchers were armed. None resisted.

Confrontation at the bridge

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. learned about what happened and called on clergy to join him in Selma for a Minister’s March. The March was scheduled to begin on Tuesday, March 9, 1965. On March 8 a court order halted further marches. Dr. King led a group of marchers from the church and over the Edmund Pettus Bridge where they stopped, prayed, and sang freedom songs. They then turned around and marched back to the church. This event came to be known as “Turn-Around Tuesday.”

That evening, Rev. James Reeb from Boston, was brutally beaten by members of the Ku Klux Klan and died two days later. As a result, President Lyndon Johnson endorsed the march on live television and submitted legislation that was to become the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

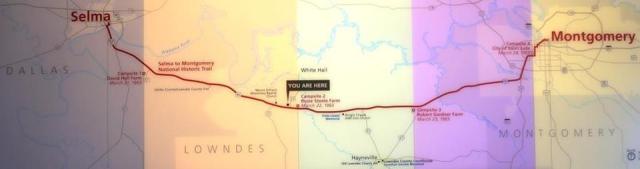

On March 21, 1965, 8,000 supporters gathered at the Brown Chapel A.M.E. Church and began marching to the Lowndes County line. From that point only 300 people were permitted to march in the road from there to the Montgomery County line where others were free to join.

The fifty-four mile march along Highway 80 took five days. Finding camping spots was a challenge as most property along the route was owned by white farmers. David Hall, a black farmer, provided the first resting place. Crews of volunteers traveled ahead of the marchers to set up that night’s camp. Others provided security and first aid. Mrs. Rosie Steele and Robert Gardner allowed the marchers to stay on their land each of the following two nights. On the final night, they stayed at the City of St. Jude, a catholic social services complex at the edge of Montgomery. The size of the group was no longer restricted so now others could join, and many did.

On the last day of the march, 25,000 gathered at the steps of the Alabama State Capitol Building in Montgomery. They were prevented from climbing the steps. The Governor was nowhere in sight and did not acknowledge them. The speakers stood on a flatbed truck to address the crowd. Armed troops lined the capitol steps behind them, standing as an impenetrable wall. After the speeches and singing “We Shall Overcome,” the crowd dispersed.

Still, the violence didn’t end. That evening four Klansmen murdered march volunteer Viola Liuzzo on Highway 80. She was a young white woman helping transport people home from the march. They shot her as she drove down the road.

National Park Service Interpretive Center

After the Voting Rights Act was signed into law on August 6, 1965 white landowners in Lowndes County retaliated against black tenant farmers that registered, voted, or engaged in any voting rights activities. A tent city was erected by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and Lowndes County leaders. They provided tents, cots, heaters, food, and water, turning the tent city into a home. It took two years for organizers to help the dispossessed find new jobs, permanent housing, and start new lives.

Tent City

On a road trip a common child’s taunting question is, “Are we there yet?” Mom or dad patiently answers, “No!” a few times before putting a stop to the game.

As for civil rights, the answer to “Are we there yet” is no. But we are making progress. We may stumble along the way, get lost or turned around, backtrack now and then, but we know where we want to go.

Someday the answer to question, “Are we there yet?” will be “Yes.”

J