National Museum of Civil War Medicine

The museum has 8 galleries. I covered the first four galleries in a previous blog post. This post covers the last four galleries.

NOTE: A full-strength regiment consisted of 1,000 officers and men. Each state recruited men for its volunteer regiments. Those men were typically recruited from the same area of the state. Ideally, three regiments formed a brigade (3,000); three brigades formed a division (9,000); and three divisions formed a corps (27,000). Casualties (killed, wounded, sick, captured) quickly reduced these numbers. A regiment’s replacements often came from the same area of a state as that regiment’s original volunteers. As the war progressed, a regiment’s strength might be reduced by casualties to 200 or fewer men present for duty.

Dr. Jonathan Letterman is known as the Father of Modern Battlefield Medicine. His three-step plan is still in use today. The next three galleries give you a peek at how each step worked during the Civil War.

Field Dressing Station

Assistant Surgeon and Hospital Steward Treating Confederate Soldier |

Contents of First Aid Backpack |

The first step in the Letterman Plan took place very close to the battlefield. Prior to battle, a regiment’s assistant surgeon would find a relatively safe location a hundred yards or so from his regiment’s position. The first photo above shows a Union regimental surgeon treating a wounded Confederate soldier near the Wheatfield during the battle of Gettysburg in July 1863.

As wounded soldiers were brought back to the field dressing station, the surgeon would assess the patient, known as triage today. If he believed the soldier’s wounds were fatal he would give him something for pain and make him as comfortable as possible. For others he’d stop the bleeding, apply bandages, stabilize broken limbs, treat for pain (usually with opium or morphine), and treat for shock (usually with alcohol).

For minor injuries, the soldier would be sent back to the front to continue fighting. For more serious wounds, the soldier would walk, if he could, or be transported by ambulance, if he could not, to the second step in the Letterman Plan, a field hospital.

Field Hospital

Confederate Field Hospital |

Amputation Kit |

The field hospital is where most operations occurred. Typically, each division set up a field hospital about a mile or so from the area where its units were fighting.

Out of 80,000 operations performed during the war, 60,000 of those were amputations.

One enduring myth is that so many amputations were performed during the Civil War because the surgeons simply wanted to. The truth is quite different. The ammunition used in the infantry soldier’s rifled musket, the Miniè ball, caused devastating injuries when it penetrated the human body. If it hit an extremity, arm or leg, the bullet would deform, splinter bones, and devastate the surrounding tissue. The damage would be so extensive that amputation was the only option the surgeon had. If the Miniè ball penetrated the body core (head, neck, chest, or abdomen), the damage would often be so extensive that the surgeon had little hope of saving that soldier’s life.

As you can tell from the second picture above, there was no consideration given to sanitation or an aseptic environment. Gloves, gowns, or masks were not worn. The operating table was not sanitized. Surgical instruments were not sterilized between operations. Bloody rags were reused.

So, it’s not surprising that almost all the Civil War soldiers that underwent operations suffered post-operative infections. But it might surprise you to know that the surgeons were not concerned about that. They called the initial signs of infection “laudable pus” and considered it a positive sign of healing. They became very concerned if infection turned into a blood-tinged watery discharge with a foul smell. They called this “malignant pus”. If that occurred there were no effective treatments for infections. If a soldier needed more care than could be provided at a field hospital he would be transported to a general hospital, usually near a large population center.

General Hospital

Hospital Steward’s Medicine Chest |

Surgeon Checks on a Patient |

Civil War surgeons got the right answer but for the wrong reason in their design and operation of general hospitals. They focused on keeping the wards, bedding, clothes, and soldiers clean, not because it reduced germs and the spread of disease and infection, but because it made the wards smell good.

Medical dogma at the time stated that disease was linked to bad air – think swamp odors leading to malaria, and the stink of open sewers bringing diarrhea and dysentery.

Better food and plenty of rest certainly helped too.

Medical knowledge did advance, although very slowly. Hospital gangrene was an often fatal infection that afflicted many amputees. Dr. Middleton Goldsmith, a surgeon in a general hospital, noticed that patients in wards with pans of bromine under their beds experienced fewer cases of hospital gangrene that patients in wards with pans of iodine under their beds. He developed a very effective bromine-based treatment for hospital gangrene that drastically reduced that infection’s death rate. Advances in care and treatment resulted in a 92% survival rate for patients treated in general hospitals.

After the War

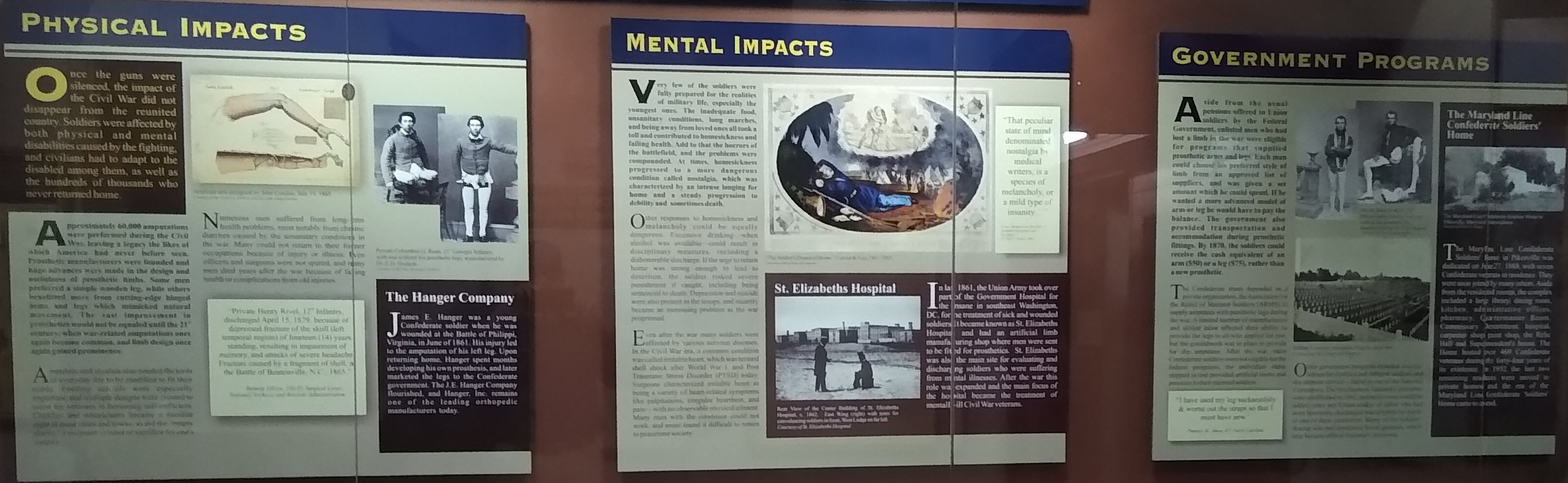

Civil War’s Impact on Veterans |

The Civil War spawned new industries. A Confederate soldier lost his leg in battle in July 1861. When he returned home he started tinkering with artificial limbs. The company he founded is still in operation today, the James E. Hanger Corporation.

Soldiers returned from the Civil War suffering from the same issues that haunt soldiers after every war: PTSD, drug and alcohol abuse, joblessness, and homelessness. In previous wars, when a veteran was discharged, he was on his own. It was up to his family and friends to help take care of him. Any problems they encountered were attributed to personal shortcomings and weaknesses.

The country’s attitude toward its veterans began to change after the Civil War, eventually leading to today’s Veterans Administration.

The post-Civil War era also saw the beginnings of social services for veterans. Both the Federal government and the states that formed the Confederacy provided their veterans with pensions if they were unable to support their families because of war-related disabilities. Old Soldiers’ homes were established to care for veterans that had no one to take care of them. Veterans also created their own social organizations, similar to today’s American Legion and VFW.

J